Digitalisation

ANNOUNCEMENT! The second issue of culturala on the theme of digitalisation is now out and available to all. Here's all you need to know about it...

Dear friends,

It’s with great pleasure that I share with you the second issue if culturala, digitalisation. This issue brings completely new critical perspectives, at least for me, despite the digital realm being nothing new in art and culture with artists being among the first to explore the medium through art and technology collaborations that Catherine Mason memorialises so well in her featured essay ‘A Short History of the Artist and the Machine.’

Our current reality is semi-digital in so many ways, something Mia Ribeiro Alonso touches on in ‘Out 2 4get’, narrating a feeling of disconnectedness that comes from the constant connectivity of today. Somewhere within this ongoing digitalisation of the world we perceive lies an existential question: what actually happens when we change the state of our stories, of our art, of our communication?

In that process of digitalisation itself, is it that we lose something? Or do we gain something? Do things change their meaning the way they do when we change the form but not the content or in other ways? And what happens when we enter that in-between space of the digital and the analogue – the space that both Isabel Bonafe’s and Sarah Lou Sasha Maarek’s art inhabit? These are the questions that the digitalisation issue explores through a myriad of different essays and perspectives from artists, writers and creatives, often in conversation with one another.

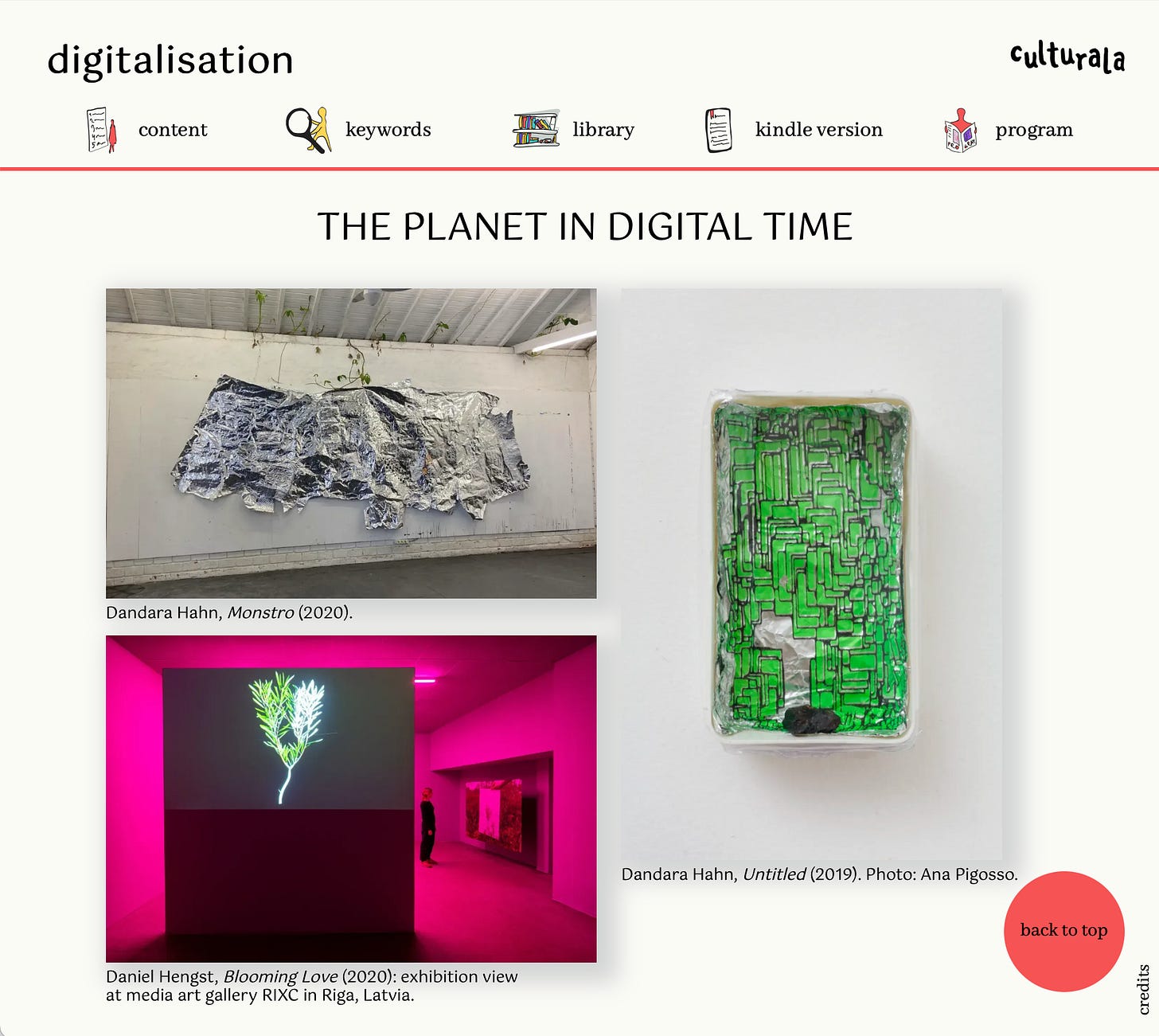

Interestingly – and unexpectedly, at least for me – these questions find their answer in the uncanny. ‘The uncanny valley,’ as Daniel Hengst explains, in conversation with Dandara Hahn and myself in ‘The Planet in Digital Time, is ‘a concept [from] the 1970s, [explored by Masahiro] Mori [who] was concerned with puppets and masks from Noh theatre, showing that the more human a puppet looks, the more affinity we feel with it. When a puppet approaches but fails to look lifelike or human, we experience something in between empathy and revulsion – that’s when you’re in the midst of the uncanny valley.’

And the uncanny comes up over and over again in the essays and conversations in digitalisation. It is the ‘uncanniness’ of the digital world that seems to intrigue us, fascinating artists throughout digital time. If the digital is uncanny, more-than-real, dead-but-alive, then the scenario of the world as we know it is also at this edge of existence. When you’re digitalising something – come with me on this trail of thought – when you’re digitalising a thought (say a tweet) or a memory (a video, photograph or insta story), you’re placing it inside a space that *feels* both human and not.

Perhaps it’s therefore no surprise that Dandara Hahn, who recently moved away from working digitally, is now creating an artist book on alien sightings. Or that Akane Kawahara, featured in ‘In a way even the Rainbow is Digital,’ creates installations with plastic under a polarising filter that shows the rainbow colours of its tension that audiences perceive as digital rather than sculptural pieces (which they originally are).

There’s another side to this uncanniness: fear. Just as without horror there is no uncanny, there is in digitalisation fear of what happens if the digital, if the robots, the machines, take over. Or, as Elspeth Walker puts it in the title to her essay (also featuring Fffirst Time): ‘Should We be Scared of AI Poets?’ For Elspeth, the question of fear concerns ethics. Seeing digitalisation as an exponential process, she argues that the digital is more likely than not to further the inequalities of our world. And it does.

Contrastingly, Hassan Bhandari writes in his essay ‘A New Era? The Impact of Emerging Tech on Creativity’ that it all just depends on how we choose to use the technology. Isabel Bonafé and Valentina Ferrari, for example, use algorithms to highlight an aspect of memory and how both we humans and the machines we use struggle to re-create broken, forgotten memories.

But, if it all just depends on what we think about this uncanny space, why can’t we find a way to make it liberating instead of limiting? Why are we furthering the very same inequalities? Daniel Hengst tries to circumvent it in his work by positioning plants – instead of the viewers – as the subject, forcing the viewer to circumvent them in their journey. Benjamin Hall, however, has a slightly different perspective. In their featured essay ‘Tiny Reminders of New Futures of the Past,’ predicts that this current digitalisation status quo means that the future will be oral. It will come back to oral histories in new situations, however digitised. Because even these new worlds tend to be folkloric – or, as I would now call it, uncanny.

And that’s what you can discover in full if you get yourself a copy of the issue, all the proceeds of which will go directly to the contributors of our third issue on memory. But before then, let us delve on digitalisation, and let me invite you to get yourself access to these pieces via culturala.org/digitalisation.

With all my love,

Maria, editor of culturala