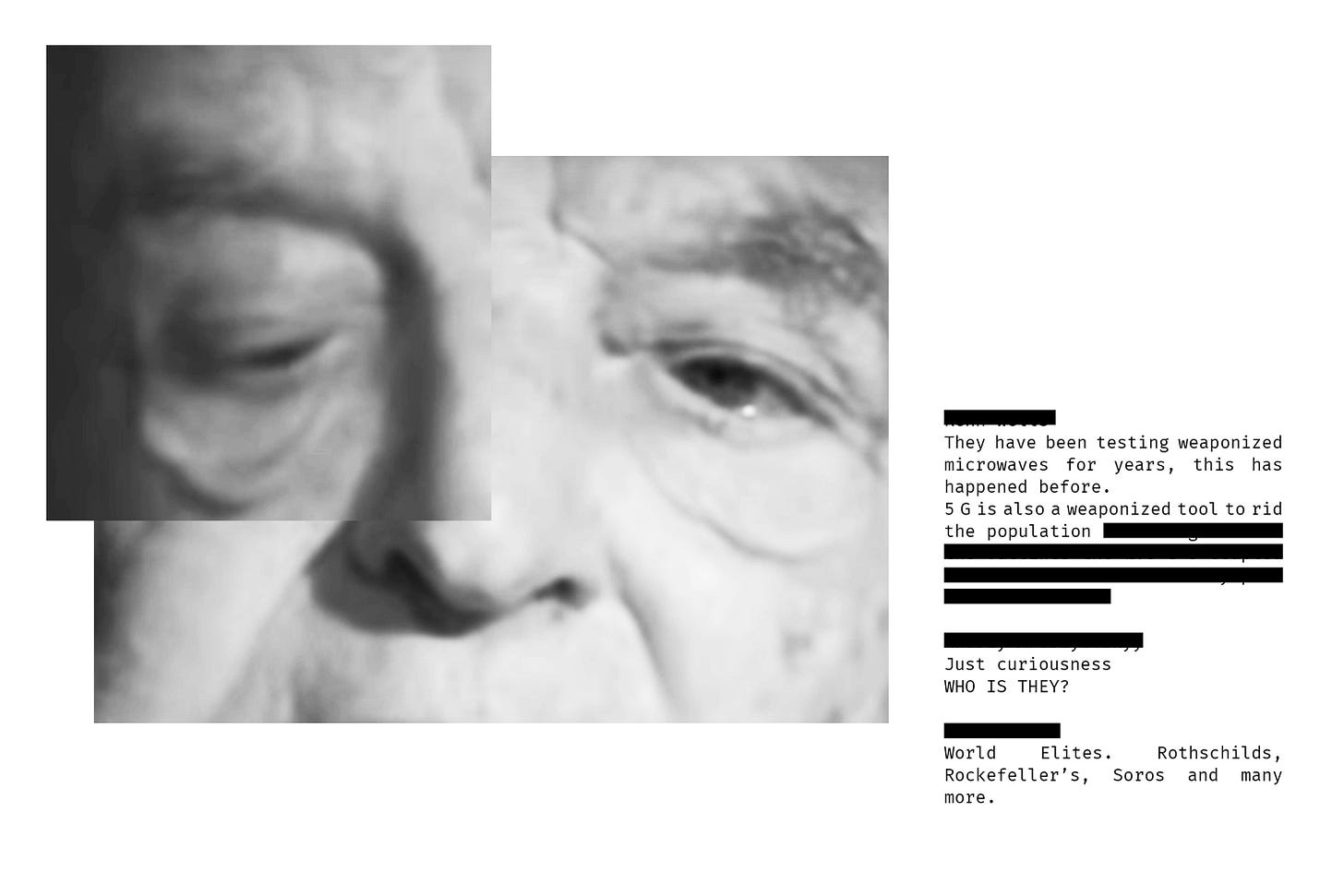

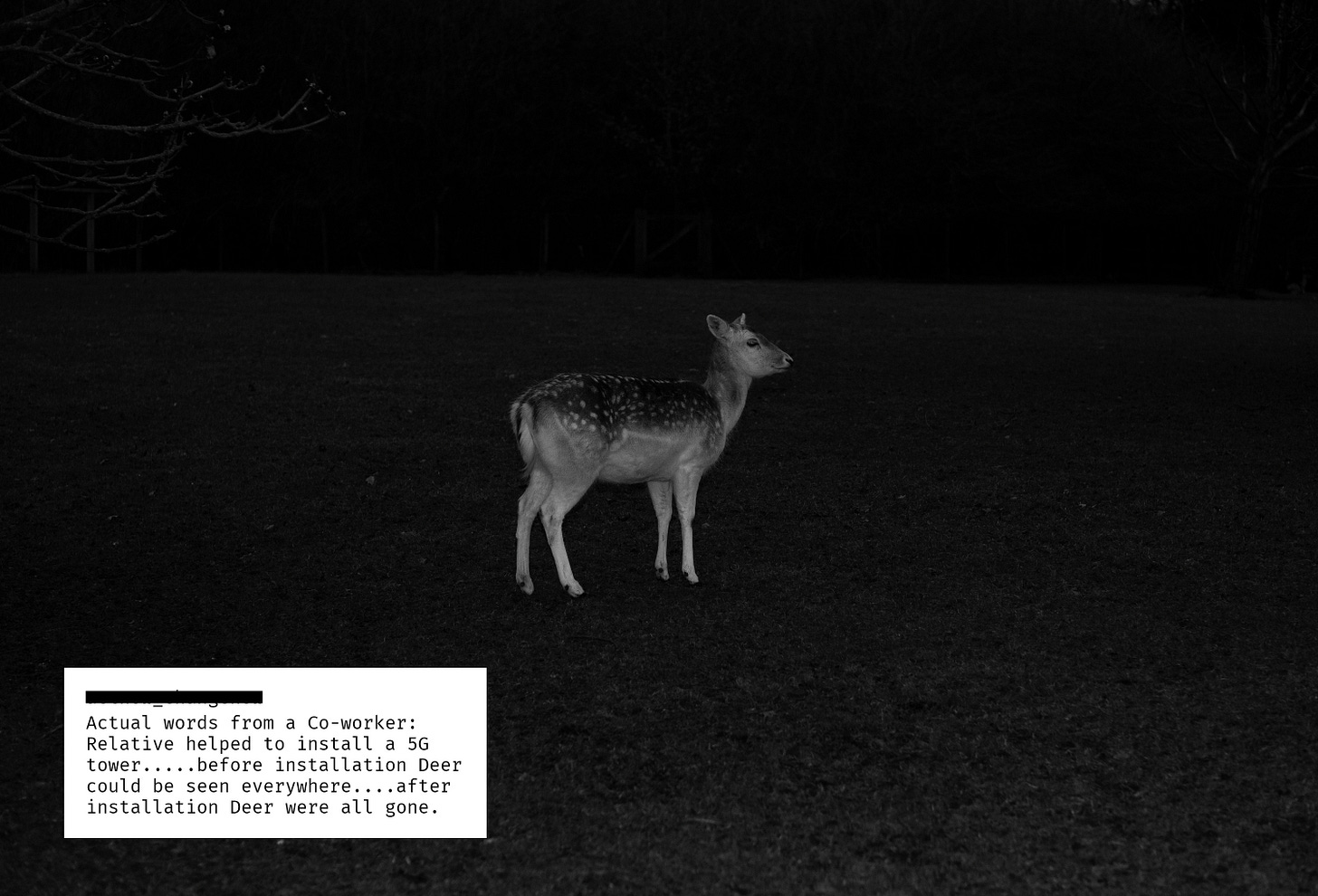

Speculative histories and conspiracy theories

A conversation on digitalisation, speculative histories and increasingly widespread conspiracy theories with photography artist Esther Gabrielle Kersley.

Dear friends,

You may have noticed some slight radio silence from our side, and that’s because we’ve taken (a well-deserved) holiday until mid-September. Nonetheless, our newsletters continue as always, and we’re most excited to introduce yet another artist working with digitalisation – this time, in the realm of conspiracy theories in the depth of the internet: Esther Gabrielle Kersley.

We were introduced to Esther, who’s a documentary photographer, by our community partners Revolv Collective some month ago. Soon enough, we became fascinated by her work in relation to digitalisation – and with The Fifth Generation in particular, an art project concerned with conspiracy theories and the internet. Maria went on to do an interview with Esther and below is what the two had to say... But, before we go on, let us just shout out to Revolv’s The Interdisciplinary Darkroom, a series of analogue photography workshops that calls ‘artists, students, recent graduates, researchers and enthusiasts engaged with photographic materiality.’ Do check it out via their website; the in-person series runs September 30th-November 25th. And now, over to Esther’s work…

Maria / culturala

Hey Esther! It’s great to speak to you; I’m very glad that Revolv Collective introduced your work to us. Could you start by telling me a little bit about your background? How did you become an artist, and what is your way of working now?

Esther

Originally, I studied Politics and Conflict Studies, going on to work at various NGOs and think tanks in the area of international security and conflict for several years. This background has informed my art practice and, in some ways, was my route into photography. In a lot of these organisations, I was the informal photo editor and I became really interested in how we communicate complex topics visually. At the same time, I was working on my own projects, both photography and documentary short films. In 2019, I decided to do the MA in Photojournalism and Documentary Photography at the London College of Communication, University of the Arts London. And then I became a documentary photographer ;)

All the projects I work on are research-based, long-form projects – so they generally take some time. I usually have an idea of something I want to explore before I start. It could come from anywhere but it’s usually something that troubles me or that I don’t quite understand. And then I begin to research this topic by reading, watching and listening to things.

So my work comes out of this research… I don’t have a set way that I make images, it comes from the topic and what I feel suits it best. I generally try to research and make images at the same time, as I find doing these things simultaneously helps me figure out what I’m trying to say and the right language to use.

culturala

It’s quite unique that you’re seeing the research and the photography in parallel, rather than doing one after the other. So, I was especially interested in a range of your projects that are based on what I would call speculative histories. Would that be an accurate description?

Esther

Yeah, I think “speculative histories” is accurate. My work is not traditional documentary photography, but I still see it as documentary as it is responding to real events, but often using fiction to do this. My work is also concerned with the truth claims of photography, and the blurred boundaries between truth and fiction in documentary storytelling. I find fiction very powerful and believe it can sometimes provide more insight, or say something more truthful, than straightforward documentary work.

culturala

How did you end up working with this kind of in-between truth and fiction of speculative histories?

Esther

I think that my reason for working in this way is twofold. Firstly, it is often a result of the topic I'm working on – I’m drawn to subjects that are harder to visualise in a traditional way because they might be taking place virtually or mentally, or haven’t actually happened, or are contested.

Secondly, I think the topics I chose to work on are a reflection of the world we live in today – and so is my approach to these topics. I see misinformation and the overload of information in our online ecosystem as one of the key problems of our time. I think growing distrust in what we see and read is a reaction to this problem, and so I believe journalists, photojournalists, documentary photographers, artists and so on need to find new ways to reach and engage people.

I believe that art is most powerful when it allows space for ambiguity and doubt. This is a slight reaction against the world of politics and the limitations of straight, rational ‘facts’ to combat complex problems that are often rooted in emotion. I’m more interested in posing questions that will encourage curiosity in the viewer, prompting them to reflect and think for themselves, rather than providing an ‘answer’.

culturala

Fascinating. Could you tell me a little bit more about how you see this new way of engaging with the false/truth scenario of the online ecosystem?

Esther

The problem of misinformation is nothing new, but the internet, and in particular social media platforms, has increased the speed and reach in which information spreads, making the issue worse. And as social media platforms prioritise inflammatory content, ideas and information that make people angry travel further, meaning online discourse has become more polarised and extreme. In addition to this, the volume of information we are exposed to today is also having an impact on not just our sense of reality, but also our attention and our ability to engage meaningfully and critically with information we come into contact with. This is the environment in which art is being made today.

culturala

So, do you think that art has a response to this since it is made in that environment? It’s an age-long view of seeing art as a kind of mirror to its society, something that is kind of partly true and partly not.

Esther

Well, in photography, the term “postphotographic age” was coined to describe how this image-saturated era has complicated how we make and consume images. I think it also offers opportunities for photographers to make work in new ways and to think more critically about photography and our role as image makers. In a world where 3.2 billion images are shared online daily, how can we avoid adding to the noise?

For me, the response is rather than trying to elicit an immediate and strong reaction in the viewer, I’m more interested in making something that will force people to take the time to engage with it, to try and figure out what they’re seeing, and what they think about it for themselves, to prompt a conversation. To be comfortable in the grey area, a place of uncertainty.

I also think that through this we can show some of the limitations of photography as a medium of truth or objectivity.

You can read the rest of this conversation via culturala.org.

With love,

Esther, Maria and culturala

You can follow Esther on instagram @esthergabrielle__ and see more of her work on her website esthergabriellekersley.com.