A digitalisation-driven climate crisis?

Editor Maria Kruglyak delves into questions of artistic responses to the digitalisation-driven impact to a world and climate in crisis. [Part 1]

Dear Friends,

I wanted to invite you today to take a step back and to re-consider the meaning of digitalisation not just as that which is the interface you see but also the physical technology behind it. It’s going to be a bit of an in-depth newsletter, so bear with me as I try to untangle what the effect of the increased speed of consumption that digitalisation brings with it might mean.

Digitalisation is, by nature, set up as a kind of matrix – an uncanny connection between things that borders between the real and unreal. What makes it work, that is, what makes the robot a robot and not a doll and the computer a source of information and not just a metal box, is the ability of electrical power to release huge amounts of stored energy in one go and in particular ways. And, just as many other digitalisation-discussions it ends up with the arrival of the uncanny. As you start to look into the power structures of how this electrical power is used and found, you end up seeing some very real and very uncanny extractivist processes that increase not only our speed of access but also our speed of consumption.

That doesn’t mean that anything is bad just because it’s digital, or that digital consumption somehow is worse than analogue. What I think is interesting is rather what we use this increased speed for. Is it just “more art, more things, more life”? Or is it also more meaning?

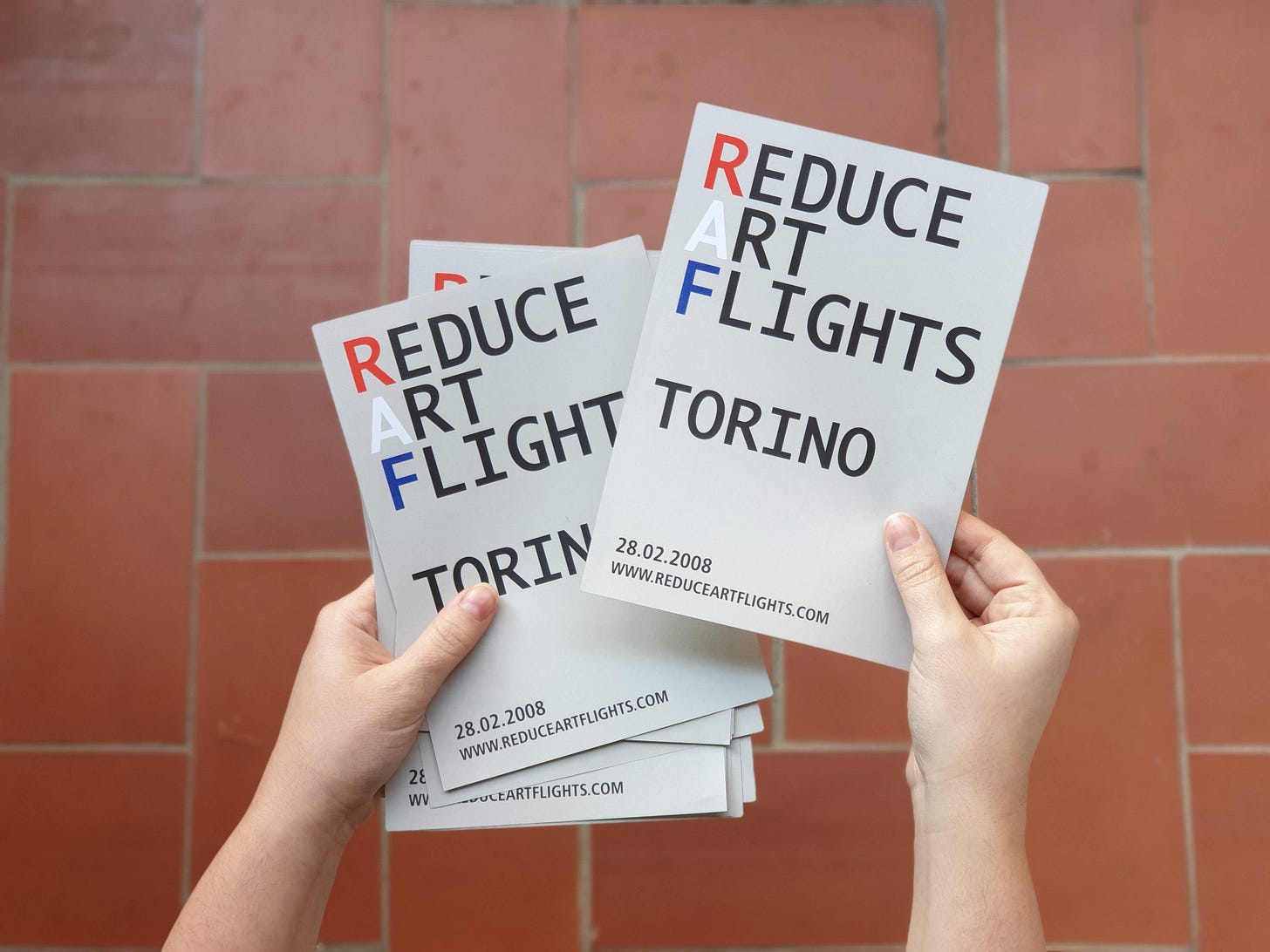

One of my favourite projects on the topic was created by Gustav Metzger as an open-source campaign-artpiece Reduce Art Flights. Since Metzger’s passing, it’s managed by Latitudes and exists as an archive and platform. RAF asks us what happens if all the art big-shots arrive to biennales and art fests in their own private jet? Is this really the only way we can get together to create art? Or is it just a performance of how much more and faster we can produce, how much more those who have can show off? As social media studies have shown, digital technologies lead to a felt pressure and need to produce, show, and be at faster and faster speeds. So, what happens then? Thousands of generators across the world once again needed to be reduced while humans are getting burnt out?

Metzger was focused on the carbon footprint, but that’s not all that matters. Perhaps, it’s rather the extractivist mindset of taking without giving, and taking fast that which the earth creates slowly. These are problems that are harder to reverse, and with increased digitalisation our demand for quick solutions seems to increase with all the faster speeds. Does anyone remember how long it used to take for a page to load in 2003 in comparison to now? Well, it may have also taken more energy to load a page back then, too. But the energy use of the world is, nonetheless, going only in one direction – up – and the way we chose to use it, how we chose to understand it and how we speak about it, defines how it works out in the long run.

Personally, I’ve recently been getting increasingly drawn into the question of lithium extraction – often called the white oil. Here in Portugal, it’s becoming a huge problem that will lead to widespread destruction if it goes ahead. You see, lithium is used in batteries, in particularly in electric car batteries, and it’s actually quite a rare material. At the moment, Europe is reliant on Chile-based and China-owned lithium mines, but since the war in Ukraine, there’s been an increased desire to become completely self-sufficient. Of course, it also helps that lithium is available in places where resistance to mining is unimportant for the global powers and where companies can profit, ignoring the fact that we can lithium-free battery alternatives like salt-based batteries, for example (available in a few years, and of course faster if there’s enough investment).

In Portugal, six lithium mining sites have been approved by the government despite incredibly active local resistance and huge extractivist impact. The biggest one is a planned open-mine pit in Barroso in Tras-os-Montes. Barroso is a beautiful agricultural heritage site that holds the source of a lot of the water supply in northern and central Portugal, practices an old cattle farming system that has been regenerating the lands for centuries and is home to the breeding site of the endangered Iberian wolf. And it’s incredibly beautiful.

If allowed to go ahead, the mine will extract all of the lithium in 11 years – a quick fix at the speed required for the digital world – that will destroy the area for centuries and most likely contaminate the underground waters, not to speak about destroying the local wildlife and agricultural practices.

The end-result of open-mining is, almost unequivocally, the creation of a huge toxic lake in the middle of the mountains. The tragic, uncanny reality is that a place that right now should be an inspiration to us for how to live has instead been chosen as a so-called “environmental sacrifice zone” – a term even the UN Special Envoy for Human Rights and the Environment has called “completely incompatible with the human right to health and ecologically balanced environment.”

All of this is well-encapsulated in Carlos Irijalba’s beautiful piece: Pannotia (Lithium) showing the broken mountain drill bits, with lithium flowing out. You know, when things break and go wrong and posion the surroundings? Well, that’s what we can be expecting here, too. It is part of a series of Irijalba’s works, shown elsewhere, that relfect on the various connections and disconnections based around the concept of Pannotia – the supposed ancestral supercontinent centred around the South Pole 600 millions of years ago.

There’s more artworks on the topic of lithium, both those shown in the same exhibition as Pannotia, Compulsive Desires, and by other artists such as Paula König’s ongoing exhibition Interlocations [para as montanhas… at Duplex AIR in Lisbon.

More on this and thoughts on whether we can reverse the increased speed of digitalisation in the next part of this newsletter series coming up, but I’d like to leave you with an encouragement to participate in the public consultation about the lithium mine in Romano by disagreeing with the government’s proposal to increase the size of the mine.

You can read about it here (where you can also find a text to copy) and access the consultation itself here until the 27th of July.

With love, and strength,

Maria